Fusion Energy on Earth

It's a long way to Tipperary

N.B. This post, originally published in October 2023, has minor formatting changes, additions and corrections. It is reposted for the benefit of new free subscribers, as background for an upcoming post.

To take the caption even further, one need not even be human to use fusion energy: Plants have been doing it for billions of years. This post is about the status and prognosis of efforts by earthlings of the human sort to mimic conditions near the cores of stars to produce heat and electricity, helping to replace fossil fuels.

Atomic energy, whether in the form of fission or fusion, seeks to release energy that is stored in atoms in the form of binding energy. The amount of binding energy per nucleon (proton or neutron in the nucleus of an atom), when plotted against the number of nucleons, is a “U” shaped curve: high for very light and very heavy nuclei, and lowest somewhere in between (actually for the isotope of Iron Fe56). So there are two strategies for extracting power: fission, in which heavy atoms like Uranium 235 are broken apart, and fusion, in which light ones like Hydrogen coalesce. Four earlier posts presented reasons why we should not be using fission, so it is only fair that at least one be devoted to fusion. The principal technical resource for the historical and plasma physics aspects of this post is the article by Wurzel and Hsu. [1]

There are many possible ways of doing fusion, and several of them occur simultaneously in most stars. During a star's stable lifetime, fusion leads to formation of various light elements, even leading to Fe. Heavier elements are also produced by fusion even though the process is energy-consuming; for that reason those processes occur only under highly energetic conditions, such as supernova explosions or neutron star mergers. The most energetically attractive processes involve the formation of Helium. There are also a number of ways to produce Helium via fusion; here are two of them:

D + D → He3 + n

D + T → He4 + n

Here, D is Deuterium, a naturally occurring, nonradioactive isotope of Hydrogen, consisting of a proton and a neutron; T is Tritium, a rare, radioactive form of Hydrogen consisting of a proton and two neutrons; and n is the symbol for a neutron. Most of the resulting energy is carried by the neutrons.

The conditions for fusion are described in terms of three parameters: the kinetic energy of the particles, the plasma density, and the amount of time available for the process to take place, aka confinement time. The minimum value of the product of plasma density and confinement time for which a net energy output exists is referred to as the Lawson criterion. The hoopla from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in December 2022 was the result of the first instance in which the Lawson criterion was met. But alas, as we will shortly see, achieving that level of performance is not equivalent to a demonstration of feasibility.

Another tool that is useful in the design of a fusion energy system is the Fusion Energy Production Rate, which is equal to the product of the number density, interaction cross section, and energy per reaction. The interaction cross section is strongly dependent on E, the kinetic energy; for a given reaction type there is a value of E for which the cross section and hence energy production rate is maximized. Of the potential reactions listed above, the second, involving Deuterium and Tritium, has by far the highest cross section at achievable levels of kinetic energy. [2] The two best funded fusion research efforts are: the LLNL inertial confinement system, called the National Ignition Facility (NIF), based on lasers; and the multinational ITER magnetic confinement system based on a Tokamak, use D-T as their fuel.

An inertial confinement reactor operates on the principle of implosion: the fuel target is subjected to a perfectly spherical incoming pressure wave that simultaneously raises the target's internal density and temperature to the levels required for fusion to take place. In the case of the LLNL system, a set of 192 lasers illuminate a cylindrical chamber with the target placed at its center.

In setting goals for and subsequently reporting the results of their experiments, fusion energy researchers at the NIF focus on a parameter called the scientific gain, Qs, of the experiment. Qs is the ratio of the energy output per fusion event to the net energy supplied[3]. As of October 2023, the record values of Qs for inertial confinement and magnetic confinement machines are 1. 53 and 0.65, respectively. According to ITER [4] a Q (the ratio of net output- to total input energy, as distinguished from Qs) value in the range 30–50 is needed for commercial viability. The best effort to date is far short in that regard.

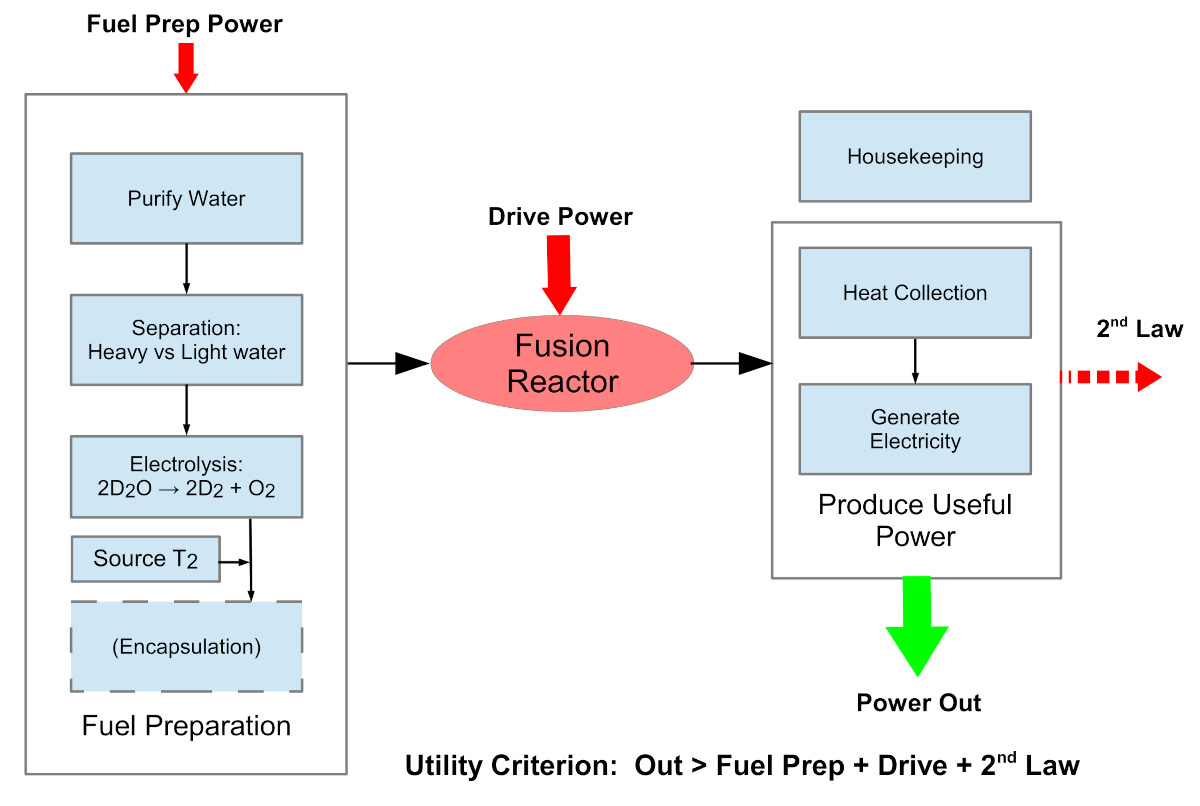

But there is more. The paramater Qs as used by LLNL describes only a small part of the energy picture. The result so proudly described by LLNL's public relations department (and the DOE) neglected to mention that the 2.05 MJ of energy that triggered the 3.15 MJ fusion event required 322 MJ of input energy [5] to the lasers. Thus an improvement of a factor of over 100 in power delivery efficiency will be required to achieve energy break even in the Fusion Reactor block of the diagram above [6].

Moreover, a practical energy producing system would have to perform a fusion event at several shots per second. [7] The current LLNL system needs about a day at minimum per run. Thus a factor of around 500,000 in the way of frequency increase is required to produce a practical system.

With the foregoing factors, it is seen that an improvement of more than a factor of 20 x 100 x 500,000 = one billion would be needed to turn the LLNL system into something that could produce electricity commercially. This factor does not include the additional energy cost of fuel preparation (including the energy-intensive electrolysis process) and the well understood inefficiency of electricity generation in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics.

Consider the Fusion System Overview, starting with the Fuel preparation block. Recent developments [8] have promised to make room-temperature separation of heavy- from ordinary water practical, so it becomes preferable to separate heavy water from the naturally occurring mix before using electrolysis to separate the Hydrogen and Oxygen isotopes. Although the Hydrogen part contains a mixture of Hydrogen, Deuterium and Tritium, it can be treated as Hydrogen and Deuterium as Tritium is found only in trace amounts. Thus the block in the diagram for sourcing Tritium. Encapsulation is applicable only to the inertial confinement process. In that case, it is necessary to encapsulate the D-T mixture in a perfectly spherical container having extremely high strength among other specific physical properties. The LLNL system capsule, which is placed at the center of a 11.24 mm long, 6.2 mm diameter focusing chamber ("hohlraum"), is a 3.1 mm diameter gold-covered diamond sphere, [9] cooled to cryogenic temperatures. [10]

The Housekeeping block reflects the need to periodically purge the reaction chamber (Consisting of Helium "ash" and about 99% of the D-T mixture, in the case of ITER, as only about 1% is fused in a given event, while the 2022 NIF achievement was 4.33% [11]) and recovery of the unused fuel in the case of ITER. It is not clear that recovery of unused fuel has even been considered by LLNL. The magnetic confinement machines use fully ionized Helium as a vehicle for heating the D-T plasma, but there are limits to how much can be present without introducing adverse effects.

The ITER is the largest example to date of a magnetic confinement fusion reactor. It is a direct descendant of the original Tokamak (Russian acronym for "toroidal magnetic confinement") conceived by Russians Andrei Sakharov and Igor Tamm based on a suggestion from the Ukrainian physicist Oleg Lavrentiev, and first operational in 1958. The first instance of fusion in a laboratory setting took place in 1934, by Mark Oliphant and Ernest Rutherford in the UK. Thus fusion in the laboratory predated both the discovery of fission by Hahn, Meitner, Strassemann and Frisch in Germany (1938) and the first controlled critical fission reaction by the Italian refugee Fermi in the US, in 1942, leading eventually to the world's first commercial nuclear power station at Windscale, UK in 1956. The slow relative progress of fusion as compared to fission is indicative of the far greater difficulty of the task.

The Tokamak is one of the two principal types [12] of magnetic confinement devices. Such machines operate by confining a plasma of the material to be fused within a toroid (loosely, a doughnut shaped vessel) by means of strong magnetic fields, then inducing an electrical current to heat the plasma to the requisite temperature to allow fusion to take place. The toroid is encased in a blanket which absorbs the neutrons produced in the reaction, heating the working fluid which is in turn used for electricity production. The ITER Tokamak will employ a toroid having a "D"-shaped cavity with a volume of 830 cubic meters, enclosed by a set of 16 toroidal superconducting magnetic coils 17 meters high and 9 meters wide. It is designed to achieve Q > 10 and produce 500 MW of power [13].

Unfortunately it is not presently possible to compare the performance of the ITER Tokamak with that of the LLNL laser-based inertial confinement system because the ITER does not yet exist. The multibillion (Dollar; Euro; Pound) project has experienced severe construction delays, most recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic and then the discovery that a recently delivered segment of the toroid was bent. The current schedule is to commence D-T experiments in 2035. [14] Once success is achieved, the system will be scaled up slightly in the DEMO system, which will explore issues related to bringing fusion power to the electric grid. [15]

Although the LLNL NIF is currently ahead of ITER in terms of demonstrating the possibility of fusion energy, the inertial confinement concept is unlikely to win out in the long run, owning not only to the need to scale up performance by nine orders of magnitude, but also, and perhaps more importantly, because of the immaturity of a system concept. Aspects that are addressed in the design of the ITER, such as how to achieve nearly continuous operation, sourcing of tritium, and how to extract the heat produced, do not appear in the material I have been able to obtain about the NIF.

At this point it is safe to predict that fusion power will eventually be possible and, though not discussed here, sustainable, not weaponizable, and reasonably safe. Estimates as to when it will begin producing power for the public vary, and I have previously gone on the record with an estimate of 50 years, for the simple reason that it seems to have always been 50 years off in my experience. Based on the research done for this post, I see no reason to alter my opinion. Aside from the timing, a major question appears to be one of economics: will fusion power be cost-competitive with other forms of sustainable energy? Another question concerns the long term availability of tritium. It is far too early to attempt answering the first question. The second will be taken up in an upcoming post.

In preparing this post, I deliberately excluded discussion of the numerous small startups' explorations of less grandiose concepts for fusion power. This was done in the interest of brevity, and also because of my impression that they are all long shots, but I could be mistaken. If you are interested in getting more information concerning many of the startups, you might consider starting here. [16]

PS: According to a recent article [17], the NIF achieved an output of 3.9 MJ in 2023, a 25.8% improvement over the result cited above. However, no corroborating reference was cited.

Notes

[2] A Python script written by Christian Hill of the IAEA is available for plotting interaction cross section versus energy for various reactions at https://scipython.com/blog/nuclear-fusion-cross-sections/.

[3] This is an unusual and self-serving definition. Ordinarily the Q of a process is the ratio of the net output to the gross input. Hence I use Qs here where appropriate to avoid confusion.

[4] https://www.iter.org/sci/iterandbeyond

[5] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-04440-7

[6] Per the conventional definition of Q the largest value achieved to date by the LLNL system is 0.00978. Strictly speaking the diagram is only applicable to a laser driven machine; for the ITER design part of the fusion energy is used to generate fresh tritium fuel. More about that in an upcoming post.

[7] https://www.science.org/content/article/historic-explosion-long-sought-fusion-breakthrough

[8] https://phys.org/news/2022-11-material-heavy.html

[9] https://lasers.llnl.gov/news/high-quality-diamond-capsule-enhanced-nifs-record-energy-shot Target and hohlraum dimensions given in [11].

[10] https://lasers.llnl.gov/about/keys-to-success/targets

[11] https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.065102

[12] https://www.iaea.org/bulletin/magnetic-fusion-confinement-with-tokamaks-and-stellarators

[13] In this case, Q is per the conventional definition: If successful ITER will produce 500 MW from 50 MW input.

[14] https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.4997

[15] https://www.iter.org/sci/iterandbeyond

[16] https://www.sueddeutsche.de/projekte/artikel/wissen/kernfusion-energie-forschung-e499361/?reduced=true and https://physics.aps.org/articles/v17/22